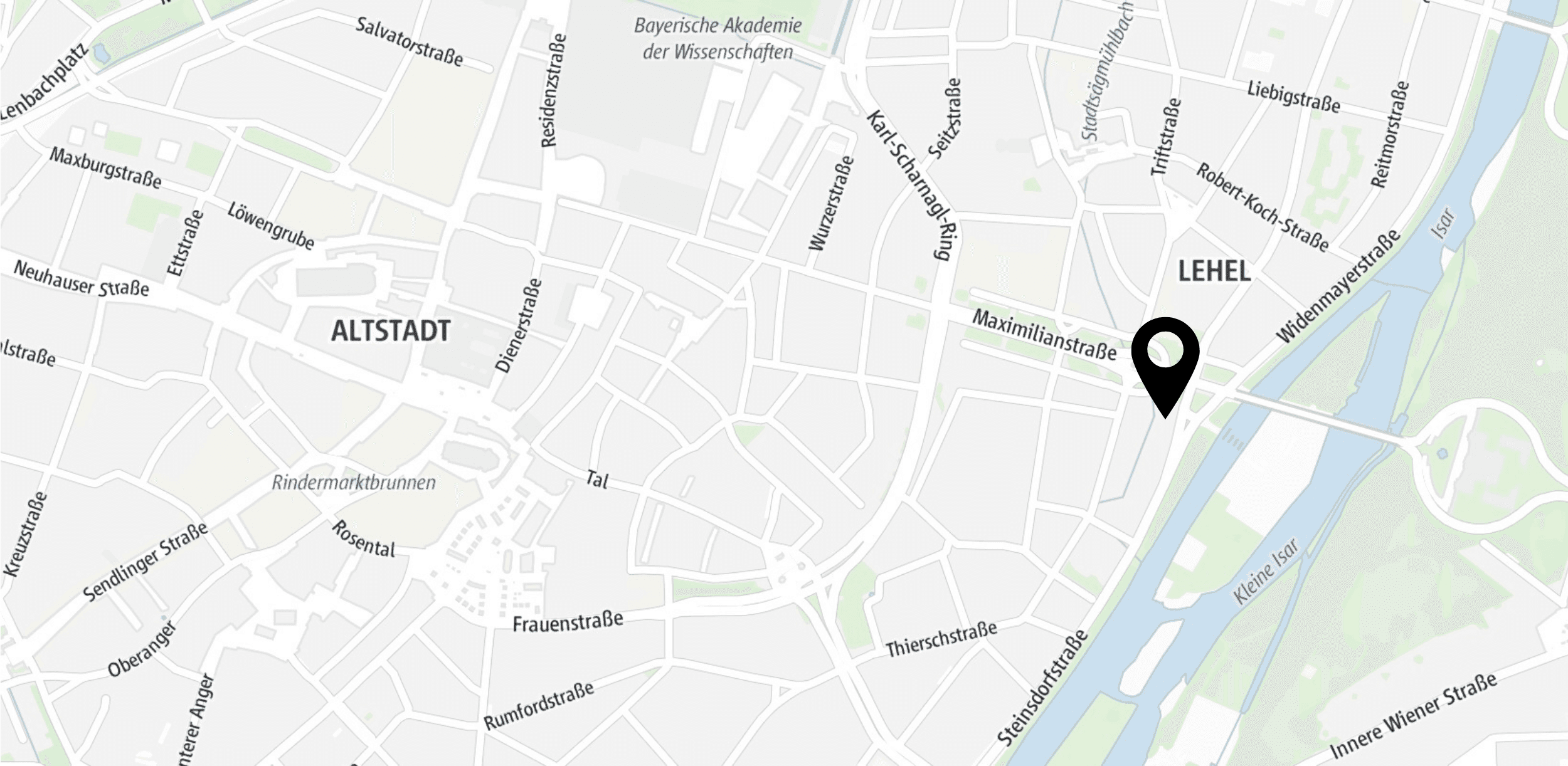

Julian Grosse is a computational linguist, associate lecturer for German language at Arden University, has worked as a language engineer at Oxford University Press, and has researched chatbots as a researcher at the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI). Today, we are pleased to share Julian's perspective for a deeper understanding of how to use LLMs such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and others in our professional and private lives.

-

Perhaps it's because we're always thinking about AI in our professional and private lives, but I've heard some people refer to you as an “AI linguist.” Are you an AI linguist?

Yes, you could say that. When we talk about computers and language, there's no getting around artificial intelligence. Innovations in hardware and software have enabled us to tackle increasingly complex tasks with artificial intelligence. This now includes human language.

So you're actually a premium translator between two worlds: on the one hand, our human language with all its nuances–such as mood, suggestion, and ambiguity–which is often shaped by individual, personal experiences, and on the other hand, you also speak “AI,” i.e., what LLMs generate.

Understanding Language and Translating from Human to Machine

I hear many people–including decision-makers–say that AI, i.e., chatbots, “understand” us. As an expert, how do you view this assumption? In what sense can we even talk about understanding with today's language models? And where does the term become problematic?

I think the term “understanding” is misleading above all else. This is because “understanding” comes with all kinds of expectations for us. It suggests an autonomy that an LLM does not intrinsically have. For me, when we talk about human “understanding,” we are also talking about things like memory, emotions, or the direct experience of the physical world. If we project such abilities onto an LLM, it prevents us from utilizing the actual and very real potential of this technology.

For example, if someone tries to get access to sensitive company data using foreign-language, threatening, or manipulative prompts, I can't rely on the LLM's common sense to recognize this as a threat. At the same time, with the right prompts, I can use an LLM to identify and report security risks and thus protect my company, in combination with other security measures.

But we shouldn't throw the baby out with the bathwater. Even though I'm reluctant to attribute the concept of “understanding” to LLMs, the achievements of this technology in the field of cognitive tasks are undeniable and will soon be indispensable from a business perspective.

Language Risks and People's Expectations of Machines

Language often seems harmless because it is so familiar. Where do you see the biggest risks when companies don't take language seriously enough in AI systems?

Language is first and foremost communication, and communication affects every business. With the enormous breakthrough of generative AI in terms of language, customers increasingly expect personal, immediate, and solution-oriented communication. If a company cannot deliver this, customers will look to the competition.

So in our language, there is no “right” or “wrong.” But we expect AI to give us the “right” answer. This expectation is also deeply ingrained in me, and I have to keep reminding myself that I will probably often be disappointed. How do you view people's expectations in their private and professional lives when it comes to the use of AI?

What excites me so much about AI is that it shows me my own lack of understanding. Often, I don't get the “right” answer from the LLM precisely when I haven't yet adequately defined “right” for myself. Most problems, both in our private and professional lives, do not have a single, rational solution. Instead, they are the product of numerous expectations, preferences, and priorities.

AI Output Quality: Hallucinations, KPIs

When text is generated by LLMs, we are quick to talk about “hallucinations.” AI providers are already working on improving the accuracy of their outputs. How do you assess this development, and could users perhaps also contribute something?

Hallucinations are an example of how our expectations of AI can be disappointed. This is because we assume that AI “understands” us. From this perspective, hallucinations are difficult to comprehend.

The problem, however, is that AI output is optimized for how likely an answer is, not how correct it is! Whether this amounts to the same thing remains to be seen. In the meantime, users are helping to make hallucinations less common through their interactions and data, thereby narrowing the gap between probable and correct in practical terms.

Practical Use in Companies

In all good companies, KPIs such as conversions, ROI, and time savings are used to evaluate how well AI is already being used. Sometimes, the extent to which “humans in the loop” still need to be involved in order to ensure the quality of AI outputs is also taken into account. Looking at this from a linguistic perspective: What criteria are used today to evaluate AI outputs, and where do you see potential blind spots?

AI outputs can be evaluated quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitative means that the KPIs you mentioned are optimized. The result is sometimes “AI slop,” i.e., masses of low-quality content that can be produced quickly and inexpensively. Qualitative, on the other hand, focuses on experts considering the content produced to be good. A blind spot is the lack of balance between the two criteria. Both quantitative and qualitative assessments are essential, especially with generative AI.

In 2025, it started with AI communicating with AI. Autonomous agents are now supposed to plan our trips and book flights for us, but not with a travel agency, but with another AI agent from a travel provider. And our AI assistant on our work PC is supposed to commission and monitor specialized agents who carry out individual steps of a larger workflow. What role does language play when AI agents interact with each other?

Machines that communicate with each other are not initially bound to human language. On the contrary, there are far more efficient technical signals for communication. Human language is essential for modern AI since it enables it to access the entire body of knowledge written online by humankind. In addition, we humans constantly need to understand the AI's generation process. And for that, we need a linguistic representation of these processes!

Looking ahead to the next two or three years, what should companies do differently today if they want to implement AI in a linguistically clean and sustainable way?

For me, entrepreneurial success with Artificial Intelligence means a fusion of technical expertise and company-specific expertise. Getting the relevant people in one room, being open to each other's expertise, learning and experimenting together with humility and curiosity–for me, these are the steps to using artificial intelligence sustainably. I see my job as a computational linguist as acting and mediating at this interface.

The Human Element in the System

Is there anything that particularly bothers you about the current AI debate, or something that you think is said far too rarely?

I think the human aspect is neglected in the debate. In the world of work, I see time and again how important human relationships are for a company. AI and automation can help us get to the heart of problems faster, more clearly, and more precisely.

And in my opinion, this core increasingly involves human issues.

Thank you for your time and your expert opinion! The topic of AI and how it can help us achieve our personal and professional goals more easily, quickly, and perhaps more efficiently will continue to be with us for many years to come. Having you as an expert at our side is enormously valuable and, in a way, reassuring.